Your Child's Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS)

Your child has a hypoplastic left ventricle. This means that the left ventricle is either too small or absent. The most common heart problem that includes a hypoplastic left ventricle is called hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS). This sheet explains HLHS.

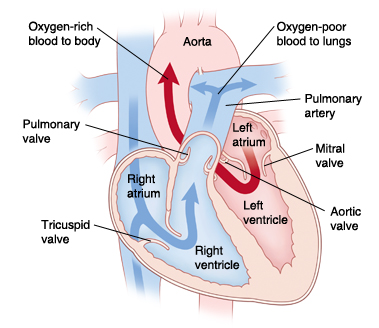

The normal heart

-

The heart is divided into 4 chambers. The 2 upper chambers are called atria. The 2 lower chambers are called ventricles. The heart has 4 valves. The valves open and close. They keep blood flowing forward through the heart and lungs.

-

How the heart works. Normally, oxygen-poor blood returning from the body fills the right atrium. This blood flows across the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. The right ventricle pumps this blood across the pulmonary valve through the pulmonary artery to the lungs. There, the blood receives oxygen. Oxygen-rich blood returns from the lungs and fills the left atrium. This blood then flows into the left ventricle. The left ventricle pumps this blood across the aortic valve to the aorta. From there, it travels out to the body.

-

Theductus arteriosus. This is a normal part of a baby’s heart before birth. It’s a blood vessel that connects the pulmonary artery and the aorta. It lets blood flow between the 2 vessels and bypass the lungs before birth. It normally closes shortly after birth. If it stays open, it’s called a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA).

-

Theforamen ovale. This is also a normal structure in a baby’s heart before birth. It’s an opening in the wall (atrial septum) between the atria. It normally closes a few weeks after birth. If it stays open, it’s called a patent foramen ovale (PFO).

|

| In a normal heart, oxygen-poor blood is pumped to the lungs from the right ventricle. Oxygen-rich blood is pumped to the body from the left ventricle. |

What is HLHS?

-

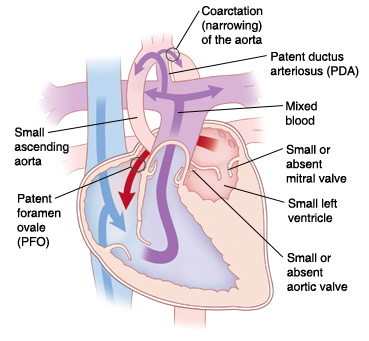

With HLHS, the left side of the heart didn’t develop correctly. The left heart structures (mitral valve, left ventricle, aortic valve, and aorta) are too small or absent. This includes the left ventricle. There may also be narrowing (coarctation) of the aorta.

-

Because the left ventricle is too small, it can’t do its job correctly. This means that oxygen-rich blood can’t be pumped to the body in the normal way.

-

Normally after birth, the PFO and PDA close. But with HLHS, they need to stay open and let blood flow through the heart and reach the body:

-

The PFO lets oxygen-rich blood from the left atrium flow through the atrial septum and mix with oxygen-poor blood in the right atrium. This causes mixed blood (blood with some oxygen) to flow into the right ventricle and be pumped through the pulmonary artery.

-

The PDA lets some of the mixed blood in the pulmonary artery flow into the aorta. This carries some oxygen to the body. The blood contains less oxygen than normal. So, your child’s skin, lips, and nails may look blue. This is called cyanosis.

-

If the ductus arteriosus closes after birth, the heart can’t use this path to send oxygenated blood to the body. This causes the child’s organs to fail. At the same time, the lungs become filled with too much blood and fluid. This leads to a problem called congestive heart failure (CHF).

|

| With HLHS, oxygen-rich blood can’t be pumped to the body in the normal way because of problems with left-sided heart structures. |

What causes HLHS?

HLHS is a congenital heart defect. This means your child was born with it. The exact cause is unknown. Most cases seem to occur by chance. Having a family member with a left-sided heart problem can make HLHS more likely.

What are the symptoms of HLHS?

A child with HLHS develops severe symptoms shortly after birth. Symptoms can include:

-

Trouble breathing or fast breathing

-

Poor feeding

-

Tiredness

-

Irritability

-

Cyanosis

-

Enlarged liver

-

Child becomes gray, cold, and the heart may stop beating (circulatory collapse)

How is HLHS diagnosed?

-

Your healthcare provider may find HLHS during a fetal ultrasound before your child is born. This test uses sound waves to form a picture of the baby’s heart. This test can be done when you are at least 12 weeks pregnant.

-

If HLHS isn’t seen before birth, signs may be found during a physical exam shortly after birth.

-

If your child's healthcare provider thinks your child has a heart problem, they will refer your child to a pediatric cardiologist. This is a doctor who diagnoses and treats heart problems in children. To confirm a diagnosis of HLHS, several tests may be done. These include:

-

Chest X-ray. X-rays are used to take a picture of the heart and lungs.

-

Electrocardiography (ECG) The electrical activity of the heart is recorded.

-

Echocardiography (echo). Sound waves are used to create a picture of the heart and look for structural defects and other problems.

How is HLHS treated?

-

HLHS is treated with surgery. This typically includes a series of at least 3 heart surgeries. In some cases, heart transplantation may be done. Both treatment choices have risks and benefits. Your child’s cardiologist and surgeon will discuss them with you.

-

In some cases, a hybrid procedure involving a combination of surgery and cardiac catheterization may be done. This may be used to treat your child in place of the first in a series of 3 surgeries. This method is typically reserved for children who are premature, have low birth weight, or have physical structures that make the traditional approach higher risk. Your child's cardiologist and surgeon will discuss the risks and benefits of this choice with you.

-

Newborns are given IV medicine to keep the ductus arteriosus open right after birth. This lets oxygenated blood reach the body.

-

Your child may need a procedure called a balloon septostomy soon after birth. This procedure may be done if the PFO is too small and there is not enough blood flow. It may be done to help until a full repair can be done. During this procedure, a thin, flexible tube (catheter) with a balloon on the end is used. It is guided through a blood vessel into the heart. The balloon is inflated to widen the PFO. Sometimes a tube (stent) may be placed to keep the hole open. This allows more blood to mix freely between the atria. More oxygenated blood can then reach the body.

What are the long-term concerns?

-

HLHS continues to be one of the hardest and highest risk heart problems to treat. After surgery, your child may have ongoing heart problems. Your child may need medicines to manage symptoms and improve heart function. Your child will need more surgery. In the long term, your child may need a heart transplant. In any case, your child will need regular follow-up visits with the cardiologist for the rest of their life.

-

In many cases, children with HLHS can be active. How active will vary with each child. Ask the cardiologist what activities your child can do safely.

-

Your child may need to take antibiotics before having any surgery or dental work. This is to prevent infection of the heart or valves. This is called infective endocarditis. The cardiologist will give you directions for this.

Online Medical Reviewer:

Amy Finke RN BSN

Online Medical Reviewer:

Scott Aydin MD

Online Medical Reviewer:

Stacey Wojcik MBA BSN RN

Date Last Reviewed:

9/1/2022

© 2000-2025 The StayWell Company, LLC. All rights reserved. This information is not intended as a substitute for professional medical care. Always follow your healthcare professional's instructions.